Warning

This write-up is very, very WIP. It’s about half done.

This page is an attempt to unpick the life of Sarah Westwood. Facts in this timeline are backed by primary sources, but Sarah was the most unreliable of unreliable narrators, so I’ve made assumptions. If you’re really interested in her I think you should skip my summary and go straight for the primary sources (transcriptions linked at the bottom of the page). Draw your own conclusions.

Early life

Sarah Westwood was born in 1822 at Brierley, just outside Leominster, youngest child of Joseph and Ann Westwood (née Smith). A few months after she was born her father Joseph, a farmer, was made bankrupt.

When Sarah was four she was adopted by her uncle, the Rev. William Smith, rector of Badger, Salop. In April 1834 William’s brother, Jacob Childe Smith, sold his household effects in Bridgnorth, and in June of the same year he died at Badger. It seems likely that Jacob’s daughter, Sarah Smith, comes to live with William Smith and Sarah Westwood when her father does.

When the Rev. William Smith dies three years later in 1837, he bequeaths almost everything to his niece Sarah Smith, with no explicit provision made for his adopted daughter Sarah Westwood. Sarah Westwood’s father, Joseph Westwood, dies in 1845. On the 1851 census Sarah Smith is listed as the head of the household, with Sarah Westwood described as her niece, not her cousin. At the end of 1855, when Sarah Westwood is 33, Sarah Smith passes away. In a report of one of Sarah Westwood’s court appearances, Sarah Smith is described as “an aunt, under whose care she formerly lived.” Taken as a whole, I believe this is evidence that Sarah Westwood’s struggles with mental health may have started long before 1857.

There are several references to Sarah Westwood being swindled out of a large sum of money that was left to her by Sarah Smith, and then in 1857 her career begins.

Timeline

May 1857

On 19th May 1857 Mary Westwood is convicted of illegally pawning a watch at Cheltenham. She is found guilty, and ordered to pay a £5 fine on top of the £5 value of the watch, or to be committed to the county gaol at Gloucester for three months with hard labour. She ends up in Gloucester gaol for three months. This is very likely her first trial.

She is described as “a person of respectable appearance, aged 25” who “belongs to Shrewsbury” and intriguingly, “has in her possession a number of papers and deeds relating to property.” She may be using her sister’s name here.

It’s very unusual for Sarah to pay for lodgings, but here we learn that “she occupied apartments at the Belle Vue Hotel where she remained three weeks”, and “she was most punctual in her payments”, until “the real character of the prisoner was made apparent to [the proprietor]”, and “she insisted upon her quitting the house.” In Oct 1861 we get the following testimony from Dr. Brooks: “He had seen her at Cheltenham sometime back, and had prescribed for her, and whilst she was under his care”. I may be putting two and two together and making five, but I wonder if she had been sent to Cheltenham for a spa cure, and maybe the reason everything was paid for those first three weeks is because somebody else had organised it. Going even further out on a limb, did Dr Brooks’ treatment make things worse, not better?

While in Gloucester gaol, she is “visited by the chaplain, the Rev. W. C. L. A. Dudley, to whom she stated she was engaged to be married to Mr. Ellis, a clergyman in Lincolnshire.”

Techniques she relied on throughout her life are already visible here: staying in a lodging-house for a few days without paying, flashing uncashed cheques to prove she can cover her debts, sending one or two items back to be resized or altered, leveraging the promise of lucrative future business to borrow money now, and simply walking away when things get too hot.

Oct 1857

Soon after being released from Gloucester county gaol, Sarah is charged on suspicion of obtaining lodging and goods by false pretences. The evidence is insufficient to establish “false pretence” on the first charge, and she is acquitted. The hearing is then adjourned. I think “the prisoner’s friends” must have paid for the “dress and other articles”, because I can’t find any reference to the second half of the hearing.

The hearing contains several intriguing elements. Her solicitor is “instructed by the friends of the accused to appear on her behalf”, and maintains she is “possessed of some six or seven hundred pounds”. He produces “a number of letters, showing that the poor woman had been most respectably brought up, and also that she had been defrauded out of a large sum of money which had been left her by an aunt, under whose care she formerly lived”, along with “a letter from the prisoner’s uncle, a gentleman in the commission of the peace, offering to provide the means for keeping her in an asylum”. [I think her uncle must be a Justice of the Peace; a local magistrate]. He also says that “she was not of sane mind or accountable for her actions”.

The obsession with clergymen is here - while in gaol she claimed to the Rev. Dudley that she was engaged to a clergyman, and once released she trades on his name. We know that her adoptive father was a clergyman, but her brother, half-brother, fiancé and husband are also almost always clergymen when mentioned.

The uncle who died is her adoptive father, the Rev. William Smith. The aunt, Sarah Smith, is not technically an aunt; they are cousins. But bear in mind this is the aunt “under whose care she formerly lived” until she was about 33, so the relationship does seem to be more like that of an aunt and a niece. So far, I have no idea who the uncle “in the commission of the peace” is. But it’s likely he made good on his promise to “provide the means for keeping her in an asylum”, because she seems to disappear for three months, and in 1864 Supt. Glenister testifies that she was in an asylum in 1859, after she was “discharged on trial”. In 1861 the Mayor of Tenby claims in a letter to The Pembrokeshire Herald and General Advertiser that “some of her relations once placed her in a lunatic asylum”, but “she was immediately discharged by order of the Commissioners in Lunacy, who visited the Asylum, from the report made to them by the resident medical officer that he had no doubt of her sanity”.

Jan 1858

Sarah next turns up in Denbigh, north Wales, cons her way into lodgings, stays a week, steals a book and decamps with her luggage to Rhyl, where she is picked up by the police. She is defended by Mr. R. Wynn Williams. She is found guilty and sentenced to 21 days imprisonment.

Although she clearly understands (due to the defence in the Oct 1857 trial) that her chances of avoiding prison are much higher if she skirts the line of false pretences and avoids charges of larceny, she still takes a book (and only volume two, at that). I guess she can’t resist, and going forward this is often her downfall: it’s much easier for the authorities to make charges of theft stick.

bef. Mar 1859

“Some time” before March 1859, Sarah calls at the home of Simon Watson Taylor in London. She has previously appealed to him for assistance by letter, and he gifted her £5. Now she turns up in person. He refuses to see her and sends her to his solicitors, who pass on £10 from Mr. Watson Taylor, investigate her story, and break contact.

Mar 1859

Sarah takes a train from Shrewsbury to Devizes, with the apparent intention of again appealing to Mr. Watson Taylor, this time at his country home. When this fails she tries to get the local clergy to “loan” her some cash, but when they get sceptical she legs it.

We learn that she is the niece of Mr. Watson Taylor’s former tutor, the Rev. Mr. Smith. (We have references to William Smith being a preceptor, or private tutor). We also get a variation on the “defrauded out of a large sum of money” story from Oct 1857 (“she had been induced by a person at Shrewsbury (where she had been living) to invest all she had in some speculative transaction, which had turned up blank, and ruined her”), and a dose of grandiose fantasy (“Under the will of the late Mr. John Taylor (a younger brother of Mr. Watson Taylor) she was, she said, entitled to £10,000”).

Oct 1859

Still trading on the name of Mr. Watson Taylor, Sarah is now claiming to be his pregnant wife, come to Aberystwith to give birth. She finds lodgings, spends a few days swindling people (with a focus on items for the baby), then cuts and runs. But one of her creditors gives chase, and “caused her to be apprehended and brought back to Aberystwith, to be tried on the charge of obtaining goods under false pretences”.

She is tried on the 11th Oct, and the Hall ‘was crowded, as the case of the “Mysterious Lady” had created immense excitement throughout the town’. She avoids a custodial sentence when the Rev. Hughes, a local curate, offers to make good the losses of the prosecutor. She is, essentially, released into his care.

The Rev. Hughes makes an application for her at the Brighton Home for Female Penitents, and she is accepted. She is received there on 14th Oct 1859. We don’t know how long she stays, but it’s less than two months.

One of the witnesses, Mrs Evans, says “I was not quite satisfied with her appearance—she was not so steady as people of her pretended rank should be”, and “soon found out she was exciteable; thought that was occasioned by drinking”. Sarah is described as “a short, swarthy looking woman, rather shabbily dressed, fond of intoxicating spirits, and her persuasive powers appear to be considerable.”

We learn a few more things about Sarah that seem likely to be true from this report. She “was lately discharged from a Reformatory”, and is “very well known in Shrewsbury, Ludlow, and other places”. We have no record of this previous reformatory stay, or any visit to Ludlow.

We are also told she “lost her parents when she was young, was brought up by an uncle, a clergyman of the Church of England” - which is at least half true - her real father outlives her adoptive father by eight years.

We also get the incredibly sniffy gem from the Shrewsbury Chronicle: “Of course, if the Rev. Mr. Hughes and Dr. Bell chose to interest themselves on her behalf, we have nothing to say” (they had something to say).

bef. Nov 1859

Sarah spends time in Brighton, spinning stories of a forthcoming marriage to a clergyman and a rich godson she needs to place at a good school. The godson is the son of Mr. Watson Taylor (who seems to have been her focus for several years by this point), and I think it possible that her fiancé (“the Rev. W. E., incumbent of Ironbridge”) is the “Mr. Ellis, a clergyman in Lincolnshire” who didn’t need a gaol bird in May 1857. She also talks her way into lodgings and a lady’s maid she can’t pay for, and orders goods from local tradesmen.

She may have a broken arm at this point, as she asks a Doctor to splint it.

Once the locals cotton on to her, “the police were called; but the lady well knew that they could not interfere in mere cases of debt”. The town’s solution is to assign a policeman to follow her around Brighton until she leaves, but before she goes we get this wonderful scene:

she undertook to pay Mr. Neale if he would go with her to a lodging she had taken in Montpellier-street, and the story goes that they started off accompanied by a policeman, and all went on well enough until they reached Montpellier-road; but as they passed Christ Church the congregation were going in for the weekly evening service, and Miss Westwood at once joined them, marched into the church, took a seat and sat there throughout the service, in which she joined with great fervour! At its close she desired the pew-opener to express to Mr. Vaughan the pleasure his sermon had afforded her. And all this time those who had followed her looked on overwhelmed with her impudence. We need hardly say that the money was not forthcoming.

Mr Torres, the master of a local prep school, admits to “being completely deceived with the manners of Miss Westwood, which were to all appearance those of a lady”, going on to say “her manners and conversation are of so peculiar and deceptive a character, as to entirely put aside all suspicion”. While at the Town Hall she takes “the precaution, however, of tossing a bundle of papers into the Town Hall Fire”.

There is some suggestion that she has been in Margate previously (“This dress, it turns out, was borrowed of Mrs. Wyatt, Cliftonville, to whom she had got herself introduced, and then made use of that lady’s name as being an old friend.”) but we have no direct evidence of this.

Nov 1859

Sarah Rosa Westwood is brought before the magistrates at Hastings, charged with stealing a letter containing halves of a £10 note and a £5 note from a fellow lodger, along with a pocket handkerchief and a pair of scissors from Ann Edgar. She had been showing the half-notes to people in order to convince them to give her credit. She was sentenced to three calendar months hard labour for stealing the pocket handkerchief and pair of scissors. Sentence is served at Lewes Gaol.

We get quite a thorough description of Sarah here; she is “tolerably well dressed” (can you hear the gritted teeth?), and “about four feet nine inches in height, thin, has her right arm bound in splinters, or in a sling, wears a black bonnet (silk and crape—trimming shabby) and thick, knitted, woollen veil, dropped half-way over the face, a large scarf shawl of a black and white mixture, a black skirt with loose drab and brown jacket. We may add that she is about 35 years of age, more or less”. This is also the only report in which “she has a cut across the throat, only seen, of course, when she removes her bonnet”, a cut which she claims was “given by a desperate and jealous lover”.

She had called on Ann Edgar under pretence of having a child to put out to nurse. Is this the continuation of the confinement story at Aberystwith?

An estimate of 35 years gives us a birth year of c. 1824 - our earliest yet (and still not quite young enough!).

Nov 1860

The Mayor of Aberystwith cautions “the gentry and tradesmen of the Borough” against Sarah, who is “now lodging in Frogmore Terrace”. She is described as “about 35 years of age, 5 feet 2 inches high, slight made, dressed in half-mourning costume, native of Shrewsbury, assuming an air of respectability”. Once again, a district that has trouble convicting her falls back on creative measures.

c. 1861

She was at Tenby “a few months back” from May 1861, “duping the charitable and imposing on the tradespeople”.

May 1861

The Mayor of Tenby, learning that Sarah is in Haverfordwest writes to the local paper to warn people about her. His letter is heavily patterned on a similar letter published in Nov 1860. He describes her as “about thirty-five years of age; five feet two inches in height; slightly made; a native of Shrewsbury, and assuming an air of respectability”, and says she is “well known to the police at Aberystwyth, Carmarthen, Shrewsbury, Swansea, Newport, Cheltenham, Bath, Hastings, and Tenby; and has also been in custody in other towns”.

c. Oct 1861

In Oct 1962, Mr Morgan Thomas, a lodging-house keeper, identifies Sarah as a woman who was “was in Clifton [Bristol] about twelve months ago, and called at his house and obtained a breakfast upon a false pretence”.

Oct 1861

On 14th Oct at Weston-Super-Mare, Sarah is accused of conning a silk merchant out £240 in goods and cash. The magistrate considers it “merely a case of liberal credit”, which I take to be a polite Victorian phrase which means “you’re a gullible idiot”. Sarah is discharged.

This is where it gets interesting. The previous Saturday evening, Sergeant Ross “received information that a female was being annoyed by a vast concourse of people in Oxford-street, and upon proceeding to the spot he found the lady present being pushed about and otherwise insulted by a mob”. He “took her to the police station for protection, and, from inquiries he instituted, discovered that she had been turned out of her lodgings on the same afternoon”. When questioned, he said “the lady was very much excited, but not intoxicated”. This is the first time we see Sarah in physical danger because of her antics.

The next day, P. S. Ross is sent for by Dr. Brookes (or Brooks). According to the doctor, she “came to his house in a drunken state, and made a great mess in his hall, and thrust herself into his apartment”. Sergeant Ross found her to be “in a very excited state through being intoxicated: her hair was dishevelled, and she was altogether out of order”. He manages to get her out of Dr. Brookes’ apartment (“but not without great difficulty”). She “walked as well as she could up and down the Knightstone-road, a crowd of people following her”. Eventually “he was obliged to take her to the station, she having by this time continued to tear her dress in such a manner as to expose her person”.

I don’t think she was intoxicated (or if she was, it was incidental). I think two run-ins with the mob was more than she could cope with, and her “very excited state” was something closer to mania. She’s pacing, she’s tearing at her clothes, she’s being hounded, she’s obviously in a lot of distress. I think this is the first time we see Sarah having a full-on attack of whatever is wrong with her.

Why was she at the home of Dr. Brooks? “He had seen her at Cheltenham sometime back, and had prescribed for her”. I think she was trying to get assistance from a doctor who was known to her, and he didn’t just call the police on her, he went on to attempt to prosecute her.

A week later on the 21st Oct she’s discharged, and it’s all very anti-climactic: it only ranks a short paragraph.

When the story is retold in Nov 1870, “she visited Weston-super-Mare, and in the name of Westwood, victimised the tradesmen to the extent of nearly £300, and hence she was hunted out of the town”. I honestly don’t think that’s hyperbole - there was a mob, and she was taken into police custody for her own safety.

Nov 1861

Sarah, using the name Rose Douglas, is charged with obtaining goods under false pretences from shops in Park Street, Bristol. She is discharged. On the following Tuesday she is brought up again, accused of stealing a gold seal from Mr. Fryer, a surgeon in Bristol. She visited him under the pretence of being pregnant, and apparently takes the seal when he is distracted. One report mentions that Sarah “answered all questions put to her in a rational manner, and betrayed no symptoms of being deranged”, but “Mr. Fryer did not think the accused was in her right mind”.

Sarah has no representation and denies the theft, claiming she found the seal on Brandon Hill.

She is remanded for an examination by Mr. Crosby Leonard, surgeon to the police, to determine whether she is insane.

A week later Mr. Leonard reports back that “she talked incoherently, said she was married to a gentleman with £30,000 a year, that she was seven months advanced in pregnancy, and that she believed she was bewitched”. This seems to clear up the last lingering doubts about whether she’s a deliberate con artist or simply mentally ill: she really believes (at least sometimes) that she’s married, or pregnant.

Letters received from “various persons in the North, where she had been previously known” give hints as to her background:

One from Bridgnorth stated that she had been previously in a good position, but that friends she formerly resided with were dead, and she had no parents. The same writer stated that subsequent conduct had entirely forfeited any assistance friends might have been inclined to lend, and added that she had been an inmate of a lunatic asylum. Another correspondent said she had been cheated out of so much property that he wondered her mind was not entirely gone.

The magistrates make an order “transferring the unfortunate woman to the Pauper Lunatic Asylum”.

In Nov 1870 we learn that she “paid Bristol a visit, and called upon a medical gentleman, in whose absence she stole a case of instruments. She was arrested, but the magistrates considered her a lunatic, and she was sent to an asylum, whence she managed to escape.”. The stolen item is a gold seal rather than a case of instruments, but I’m sure we’re referring to this event.

That mention of Bridgnorth is interesting, because that’s where Jacob Childe Smith lived almost until the end of his life. Is that where the Smith family hailed from? These reports claim she visited Bath before Bristol, but I haven’t found any direct evidence.

c. May 1862

In Feb 1863, Supt. Glenister mentions that he heard of Sarah being at Worthing “about nine months ago”.

I suspect she was actually still in the Pauper Lunatic Asylum at this point, because her next appearance, in Oct 1862, is also in Bristol.

Oct 1862

Sarah Westwood is accused on 6th Oct of “obtaining 10s from Miss Nicholson, of Rodney Place, by a false representation”. She is discharged with a stern warning by Bristol magistrates because Miss Nicholson does not attend. She claims she has returned the money.

Sarah is described as “a well-spoken female”. That a witness “could not get a look at her countenance” implies that she was wearing a veil.

It is mentioned that this is her second appearance at Bristol Police Court (her first appearance being Nov 1861). If she really has just escaped from the Pauper Lunatic Asylum, this looks a lot like begging. There’s no suggestion that she’s living at an address.

Nov 1862 (Portsmouth)

In Oct 1866, Sarah is accused of swindling several tradesmen at Portsmouth in 1862. She was lodging in Peel Street, and “Witness had known her in this town as Westwood — on the 8th of November, 1862. She was then here three weeks.”

Nov 1862 (Ventnor)

On 30th Nov Sarah is brought up under the name Edith Westwood on a charge of obtaining money and goods under false pretences. No prosecutor appears and she is discharged.

Dec 1862

Feb 1863

Edith Vernon is accused at the Hastings and St Leonards borough petty sessions of “obtaining by false pretences, from Mrs. Church, of 12, Everfield-place, a mutton chop and some potatoes, value 1s., also with obtaining by false pretences from Harriet Whitnall, of 59, Marina, some grocery, meat, bread, and other articles of food, of the value of 8s”. She is committed for vagrancy and “imposing on certain persons”, and is sentenced to one month’s hard labour. Sentence is served at Lewes Gaol

Sarah is described as “a middle-aged female, somewhat meanly attired”. She claims to be “a clergyman’s daughter”, and that she has “a brother who was a clergyman”. When questioned about Sarah’s clothing, one of the witnesses said “her talking recommended her to me”, which presumably means she sounded middle-class, even if she didn’t look it.

This is her standard MO (lodgings, middle-class shibboleths, delayed luggage, promise of a long engagement) but the court convicts her of vagrancy. Is the difference in her crime down to her appearance?

Apr 1863

In Oct 1864, William Glenister, superintendent of the Hastings police, testifies that on 19th of April 1863 Sarah gave the name Rose Westwood.

Jul 1863

Sarah Westwood is tried at Hastings Quarter Sessions, and given a sentence of one year’s imprisonment with hard labour for stealing a flannel waistcoat. Sentence is served at Lewes Gaol. She is warned that “if she were brought before any other tribunal on a future occasion, beyond all question she would be sent for penal servitude”.

Sarah is described as “notorious”. As she is leaving the dock, she says “she had been sent to prison innocently twice before”.

If you don’t include the vagrancy charge, she’s right - one 3 month sentence and one 12 month sentence in six years. I think the system’s been quite lenient with her up to this point, considering how prolific she is. Of course, this may be because what she’s doing isn’t quite criminal.

Jul 1864

Sarah is released from Lewes prison on 7th July, 1864. She seems to disappear for a couple of months. Back to Shrewsbury?

Oct 1864

After being remanded in custody for six weeks, Sarah Rose Westwood is brought up in Margate on two charges. She is found guilty on the charge of obtaining, by false pretences, ladies’ clothing to the value of £3 7s from Mr. Rapson, a draper. A second charge, of feloniously stealing a lady’s leather bag, value of 10s. 6d., the property of Isaac De Bock Kennard, was withdrawn. Sentencing on the first charge is postponed until the next sessions.

She “was undefended, having written to several solicitors, but being unable to get any of them to undertake her case”, which suggests to me extreme notoriety or, more likely, a lack of funds. She may have engaged another maid, but I think it more likely this is just part of her story.

Sarah claims to a shopkeeper “that she was only 24 years of age, but had lost nine brothers and sisters in six months”. On the stand, she states that it “was true she told the shopwoman her father was a clergyman; and so he was.” When asked directly by the court what her name is, she replies “Vernon”. Superintendent Glenister of Hastings Police appears not to object to this, saying that in 1859 she was “assuming” the name of Westwood.

Supt. Glenister “believed the prisoner was the daughter of a clergyman, deceased, and was of a respectable family in Shrewsbury. She had been an inmate of a lunatic asylum”.

The final newspaper report is the most interesting one. The Recorder “had rather a long correspondence with some persons acquainted with the prisoner’s previous character”, learning that “she had been in a state of destitution whenever she had committed these offences”, and “she had been an inmate of a lunatic asylum”. As a consequence he “did not think it necessary to prolong her imprisonment; and he only hoped she would at once proceed to Shrewsbury, and apply to the person who had in his hands some money with which he might assist her”. As she has no money, he advances her £1 for travel expenses. This man (“W. H. Bodkin Esq.”) shows real humanity towards her. The only other court that gets close is Bristol in Nov 1861, which takes the time to have a doctor to examine her.

I think the “one day’s imprisonment” mentioned in later records is just a procedural formality, to ensure her guilty verdict is written into the official record.

Jan 1865

The reports here are a little confused, and this is my best guess. We’ve returned to Brighton.

- 21st Dec—11th Jan: Sarah rents a furnished sitting-room and bedroom at 35 Grand Parade, a lodging house run by Mary Frances

- 11th Jan: She leaves Mrs Frances’ house on the morning of the 11th without giving notice, taking a towel with her

- 11th Jan: When she returns, Mrs Frances refuses to let her in, and “a few things belonging to her were handed to her out of the window”

- 11th Jan: Sarah rents a furnished sitting-room and two bedrooms at 94 Queen’s Road, a lodging house run by Elizabeth Goodwin. She agrees to pay weekly, in arrears

- c. 11th Jan: She hires a fly to take her to Littlehampton. While there she engages a servant girl

- 11th Jan: She borrows a night-gown from Mrs Goodwin

- 11th Jan: A servant joins her at about 11pm

- 12th Jan: Sarah and her servant leave that morning without giving notice

- 12th Jan: After she leaves, Mrs Frances’ towel is found in a drawer in the bedroom she occupied

- 12th Jan: After she leaves, Mrs Goodwin’s night-gown is found to be missing

- 12th Jan: Again she returns to her lodgings, and this time Mrs Goodwin refuses to let her in.

- 12th Jan: Sarah stays the night at the Bedford Hotel1

- bef. 15th Jan: She hires a fly to take her to Lewes. While there she calls on the Deputy Governor of Lewes Gaol, William Sanders, to “thank him for his kindness to her during the time she was confined there”

- 15th Jan: Sarah is arrested at 49 Norfolk Square at about 9.15PM. When charged with stealing a towel, she says “If anybody lends you anything, that’s not felony”

- 15th Jan: The missing night-gown is found in her bedroom at Norfolk Square

There are two charges, one of stealing the towel and one of stealing the night-gown. Although she must have run up plenty of debts (“Prisoner paid no money in advance”), not least to the servant she borrowed money from and who never got paid, they’re not foregrounded in these reports at all. The authorities must be pinning their hopes on the theft charges.

Sarah’s defence in the case of the towel is that she was lent it (“If anybody lends you anything, that’s not felony”), and that she was going to return it, but Mrs Frances told her to sling her hook (I may be paraphrasing slightly here). She is acquitted.

In the case of the night-gown, her defence is that she took it to wash, and she intended to return it. She is found guilty and sentenced to 18 months hard labour. Sentence is (partially?) served at Lewes Gaol.

Given the magistrate’s comment in Jul 1863 that “if she were brought before any other tribunal on a future occasion, beyond all question she would be sent for penal servitude”, I think eighteen months hard labour might be yet another “last chance” - in the mind of the magistrate, at least.

Sarah’s comment that she was “followed by the police everywhere” and the fact that landladies keep refusing to admit her after she’s been out for the day may be related. I think the Brighton police, knowing they can’t do much about the debts she runs up, are doing everything they can to make her unwelcome in the hopes she’ll move on.

Sarah has again engaged a maid, and has borrowed 5s from her, “all the money from her servant what the young woman had”.

When asking for bail, Sarah says: “I consider it a “hard case.” I have been three times in a lunatic asylum and I do foolish things sometimes. I think it very hard that I should be again shut up in gaol without having an opportunity to recover my health. I am willing to pay for the articles or to be bound over to appear at any future time, but not to be shut up in a gaol. Will you allow me bail?”

This “I do foolish things sometimes” is the only commentary we have from Sarah on her own illness. I wonder how she came to terms with it. The comment that she “went away the next day, with the night-gown on” is interesting - to me it implies some quite disordered thinking, but at the same time she must be functioning at quite a high level, after all “she had swindled more tradesman here than any other person that ever came into the town”.

We don’t know whether she is bailed or not, but I feel it’s unlikely. We have confirmation from Mr White that “this was her third visit to Brighton”, so I think I’m still missing one. We also have three asylum stays at this point, where I only have two.

We have another description of Sarah: “It appears that she is about 28 years of age, 5ft 1in in height, fair complexion, dark brown hair, slight make, born at Shrewsbury, is of good address, having been educated for a governess, and appears to be in somewhat delicate health. She is believed to be dressed in dark clothes.” (She’s wearing well, despite the prison time - she’s actually 42 at this point). She again mentions that she is a clergyman’s daughter. At the hearing: “I have a weekly allowance of £4, and I am willing to pay for anything that is missing. I pay my way wherever I go.”. Presumably this allowance is from “her guardian, a solicitor at Shrewsbury”.

Sept 1866

Sarah is released from Lewes gaol on 15th September, 1866.

Oct 1866 (Southsea)

Two days after her release from Lewes gaol Sarah is in Southsea, obtaining a dozen bottles of Burton ale through false pretences. On 24th Oct, Sarah is tried (other charges having been dropped). She has counsel this time, and the charge is quashed because the indictment fails to properly accuse her of lying in a way that fits the legal definition of false pretences.

She is described as “a young woman of respectable appearance” staying at 5 Dover Terrace, Southsea (south side of Osborne Road) under the name Douglas. Interestingly, she uses a prescription as a form of ID (“You see my name on the prescription—Miss Douglas”.) A couple of the newspaper reports here are extremely detailed, and give the best descriptions we have of Sarah’s day-to-day life.

Oct 1866 (Ryde)

Ryde. No other details, as her “little game in Ryde was fortunately discovered in time”.

As she’s discharged at Southsea on the 24th Oct and she’s in custody at Newport by the 31st Oct, there’s a pretty narrow window for her to be in Ryde.

Nov 1866 (Newport)

Sarah is charged with obtaining goods by false pretences at Ventor, and is charged at Newport, but it is reported later the same month that “she managed to compromise the matter with the accusers, who refused to prosecute”.

The Isle of Wight Times seems to think her real name is Rabbitt.

Nov 1866 (Southampton)

A couple of weeks later we’re in Southampton, and Sarah Westwood is charged with obtaining a quantity of goods under false pretences from Mr. Axtell, of Prospect Road. She is represented by a local solicitor, Mr. Leigh, and she is committed for trial at the next quarter sessions.

At the Southampton Quarter Sessions on 7th January 1867, she offers no defence to the charge, is found guilty and given six months hard labour.

Here, Sarah is “a well-dressed, lady-like, and middle-aged female”, she “is most respectably connected, and has an income of two guineas per week. Her genteel manners and address are well calculated to deceive”. She “was as self-possessed as ever, and treated the charge with perfect indifference. She was dressed in a most faultless manner, and her bearing was in keeping with the aristocratic titles she had from time to time assumed.” At the Quarter Sessions, the Recorder mentions that she is “a person of independent fortune”. By this point she is so notorious that her appearances attract crowds.

Nov 1867 (Southampton)

At the close of the year we’re still in Southampton. Sarah is “charged with obtaining food and lodgings at Kelway’s Hotel by false pretences”, and ends up in front of the local magistrates again.

Given that she “has only just been released from gaol”, but she should have been released four months ago, is it possible we’re missing an event between Jan 1867 and Nov 1867?

Her chosen alias here is Sarah Rabbits, rather a departure from the Hon. Digby Chicken Caesar-style aliases she’s been favouring lately.

Interestingly, she writes to Mr. Chitty of Shaftesbury, to defend her and he appears for her in person. He basically promises the court to get her out of town by sundown, and they discharge her.

Nov 1867 (Ryde)

Well if Sarah took that train, she got off at the next station and came straight back. Just eight days later she is “brought up on remand on a charge of stealing a cloth jacket, two petticoats, and a cameo brooch”. She’s denied time for Mr. Chitty to get there, but it “was fortunate for her that this request was refused by the bench, as no solicitor could have handled the case so dexterously as she did. Indeed, so well did she manage it that the magistrate did not consider that there was sufficient evidence to warrant him in committing her.”

It seems Sarah’s on fire today. And then the same day, in the same town she takes “lodgings in Simeon-street”, and orders “a fire with tea and refreshments”. The landlord cottons on and boots her out, and she apparently heads for Ventnor.

Warning

CHECKS COMPLETE UP TO HERE

1869

“The details of her conviction in 1869 at Dorset Quarter Sessions, for fraud on Messrs. Lock and Marshall, of Blandford, will be found recorded in our papers of that time.”

“She was convicted at Dorchester under the name of Edith Florence Howard, a fashionable name at Blandford.”

Nov 1870

Sarah walked from Dorchester to Weymouth (~8 miles) a week after she was let out of prison at Dorchester.

At Weymouth, we see the same pattern as before - take lodgings, order goods (including a bedstead), make grandiose claims. There are several charges here, spread across several tradesmen. She is committed for trial at the next Quarter Sessions.

Sarah has in her possession two letters from an M. C. Weston, a solicitor in Dorchester. He is, in polite Victorian terms, telling her to go back to Shaftesbury before she ends up in prison again, and that there’s no way he’s taking her case. She should find someone else - anyone else. This solicitor addresses her as Miss Westwood.

By this point, Sarah is characterised as “one of the most notorious swindlers in the country”.

In her defence, she claims that it has been arranged by Teece and Corser, her solicitors at Shrewsbury, that she should have three guineas weekly for six months. M. C. Weston didn’t know about the three guineas, which is why he told her to get lost. She “wished the public wholly to know she had been in prison seven years, and three times in a Lunatic Asylum. She had only been out of prison a fortnight for seven years”, and “the three asylums were Shrewsbury, Bristol, and Abergavenny. She had no parents living, but had a brother and half sister”.

The superintendent of police in Weymouth looks into her background, and discovers:

- She is a native of Brierley in Herefordshire

- She has a sister living in Leominster

- She “belongs” to Shrewsbury, and it is supposed that she has friends there

- Her parents are highly respectable in middle-class society (note: present tense)

- In 1860 she gave her age as 35 (giving a birth year of c. 1825)

- She is 5ft. 2in, slightly built, and has something of a cast with her eye

- She has been in custody at Aberystwith in Cardigan and at Tenby in Pembrokeshire for obtaining goods by false pretences. These cases were not considered to come within the criminal law, and were withdrawn.

From our point of view Sarah’s story is starting to draw to a close now - not because she doesn’t have a lot of life left yet, but because the system’s had enough of her, and it’s started to hand out progressively heavier sentences. So we’re going to start to see longer and longer gaps between her appearances in the record. She now disappears into gaol for four years.

Oct 1874

Back in Southampton, Sarah Edith Westwood is charged with failing to notify the Superintendent of Police of her arrival in town within forty eight hours. She had been liberated on a ticket-of-leave part-way though a sentence of five years’ penal servitude.

Intriguingly, “she had been levying black mail on lodging-house keepers”. Was that what she got five years for, or was it what she was doing in Southampton? The text isn’t clear.

She is described as being “of good connections and education, being a clergyman’s daughter”.

1876

Bristol. Ten years penal servitude.

Oct 1883

Sarah Westwood is remanded by the Clevedon Bench on the charge of obtaining money, food, and lodgings, value £5 10s, by false pretence.

She is described as “an elderly ticket-of-leave woman”, so I’ve missed something significant between 1874 and 1883.

Nov 1883

Bristol. Ten years penal servitude. The offence doesn’t seem much worse than many others, the system’s just lost patience with her. She is claimed to be 40 here, giving a birth date of 1843 - which is unlikely, as she would then be 14 at the time of her first offence.

1893

Sarah fails to report herself, as per the terms of her ticket-of-leave. She claims to be a widow for the first time, and her age of 58 gives a birth year of c. 1835.

Jun 1894

Stealing flowers at Shrewsbury. Discharged with a caution, mainly because they couldn’t figure out who the flowers belonged to. She refuses a place at the workhouse.

Mar 1895

A vagrancy charge at Ironbridge, about 15 miles east of Shrewsbury.

Apr 1900

WESTWOOD—April 14, at the Atcham Union Workhouse, near Shrewsbury, Sarah Edith Westwood, of the parish of St. Mary, aged 68.

This age (68 in 1900) aligns perfectly with her claimed age in the very first entry in the timeline (25 in 1857).

List of alises

- Bessant, Fanny

- Douglas, Miss

- Douglas, Mrs. Colonel

- Douglas, Rose

- Harcourt, Hon. Madeline

- Howard, Edith Florence

- Howard, Elizabeth Florence

- Neville, Gertrude

- Price

- Purton, Edith Vernon

- Rabbits, Eliza

- Rabbits, Miss

- Rabbits, Sally

- Rabbits, Sarah

- Roberts

- Rose, Sarah

- Stevens, Mary

- Taylor, Mrs Watson

- Taylor, Rosa

- Taylor, Sarah Rose

- Vernon, Edith

- Vernon, Edith Harcourt

- Vernon, Sophia Edith Harcourt

- Welby, Miss

- Weston

- Westwood, Edith Florence

- Westwood, Mary

- Westwood, Sarah

- Westwood, Sarah Edith

- Westwood, Sarah Edith Caroline Constance

- Westwood, Sarah Rosa

- Westwood, Sarah Rose

- Westwood, Sarah Rose Edith

- Wood

- Wyndham, Miss

- Westhead, Miss

- Young, Miss

My thoughts

I first ran across this Oct 1866 report of Sarah “obtaining a dozen bottles of Burton ale at Southsea, under false pretences”, while researching an amazing pub crawl. The combination of “a dozen bottles of ale” and “clergyman’s daughter” caught my eye.

The first reports I found painted Sarah as a charming, almost roguish heroine in the modern mould: a young, educated woman of independent means, flitting from one fashionable seaside resort to another, leaving a trail of slightly dull, outraged tradesmen in her wake. I had the impression of someone having fun while thumbing her nose at Victorian society.

But as I dug deeper, it became clear she had serious problems. Sarah’s “fun” was never sustainable, and she couldn’t quit while she was ahead. As her antics attracted increasingly harsh punishments they appeared less like rebellion and more like compulsion. Her inability to evade the attention of the law, even when facing serious consequences, suggested deeper issues. The reports from her later years paint her as a woman whose compulsion to deceive had utterly wrecked her life.

Looked at from our perspective, Sarah’s trajectory seems both inevitable and tragic: a decades-long descent from a charming, insouciant grifter to a desperately poor, often homeless offender who could never escape her own compulsion to indulge in grandiose, risky behaviour.

Her compulsions seem, to me, to be rooted in a craving to be accepted by the class she emulates. She never seems happier than when she’s being invited to tea by clergymen and colonels. It reminds me a little of the suicide of Robert Henry Marshall, who apparently shot himself because “his father, who was in business as a house decorator, had a reverse of fortune, and since then the deceased had to obtain his living by manual labour”. The Victorian obsession with class really did a number on both of them.

I do wonder if she was suffering from bipolar disorder. Maybe we’re only seeing the manic episodes in the record because the depressive episodes don’t generally result in her breaking the law. In 1859 a newspaper article mentions that “she has a cut across the throat, which she says was given by a desperate and jealous lover”. Are we looking at a suicide attempt there?

Notes

It does seem that she has easier access to funds for a few years after 1864. What if the “deceased” father in Oct 1864 is only recently deceased, and around this time she starts receiving an allowance? This would explain her claim that “she received money weekly from her guardian, a solicitor at Shrewsbury” in 1865, and her being able to access counsel, make good with tradesmen, and most tellingly her faultless dress in 1866. In 1867 a solicitor from Shrewsbury promises to take her out of Southampton, and 1870 it has been arranged by Teece and Corser, her solicitors at Shrewsbury, that she should have three guineas weekly for six months.

Did she tend to stick to seaside towns because the traders there were easy marks due to the high turnover of well-heeled visitors, or was it because she wanted to emulate those well-heeled visitors?

I wonder if she even understood why she did what she did. By 1874 she’s so well known she’s basically being jailed just for turning up.

It’s a story that’s going to end in tragedy - you can see her move from “fair young woman” to “fashionable middle-aged woman” to “frail elderly woman” throughout the newspaper reports, and she’s already being described as “an elderly woman” around the age of 48.

Oof. I’m very much no longer enjoying it. That’s rough. I’m really coming around to the idea that she doesn’t understand.

She’s middle-aged again in 1894 - I’m oddly thankful for this. Here, she’s returned to Shrewsbury and she’s obviously out of money, and either too old or too notorious to pull of any more scams.

It’s not a rare name, but there’s vagrancy charge in 1895, and a death in the workhouse in April 1900. They’re both near Shrewsbury, so I consider them likely.

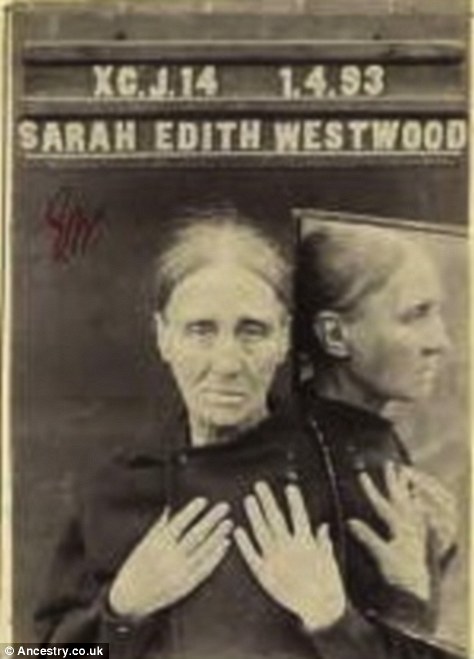

Wow. I didn’t expect to find a picture of her.

Future research

- Records of Bristol’s Pauper Lunatic Asylum, 1861-62 link

- Fill out family background

- Check for Rabbits/Rabbitts surname in Brierley/Leominster/Shrewsbury

- Investigate letter from Bridgnorth in 1861

- Check records of sundry petty sessions

- Records of Gloucester County Gaol, 1857

- Rev. W. C. L. A. Dudley - surviving papers?

- Sarah Smith - will?

- How did she know “Mr. Ellis, a clergyman in Lincolnshire”?

- Are “the Rev. W. E., incumbent of Ironbridge” and “Mr. Ellis, a clergyman in Lincolnshire” the same person?

- Records of Shrewsbury asylum, probably 1857

- Records of Abergavenny asylum, 1857-1870

- Better photo

- 1861, 1871 and 1891 censuses are missing

- Several times, a solicitor is drafted in from Shrewsbury. Do they all work for the same firm?

- What’s happening in that gap between Jan 1858 and Apr 1859?

- When did her mother die?

- When did she move to Shrewsbury?

- Sarah Smith’s will

- Research magistrates who cared, with an eye to surviving paperwork

- When was she in Bath?

- Prove link between Watson Taylor and Smith family

Footnotes

-

I’ve stayed here! At least, I’ve stayed at the Holiday Inn that now occupies the site. Right on the seafront, great views. ↩